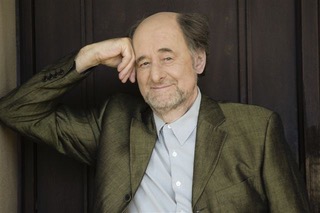

28th November 2022 For fifty years Roger Norrington has been at the forefront of the movement for historically informed…

Sir Roger Norrington on Schumann’s Symphonies

Editor – Dr. H. Baxter ISSN 2754-4850

28th November 2022 For fifty years Roger Norrington has been at the forefront of the movement for historically informed…