Image: Tanya Rosen-Jones

1st February 2023

Taiwanese-American conductor Tiffany Chang helps musicians feel valued, seen, and fulfilled, while guiding arts leaders to do so too for their organisations. For her exceptional artistry, formidable versatility, and unshakeable integrity, Chang garnered recognition through two Solti Foundation U.S. Career Assistance Awards, the OPERA America Grant for Women Stage Directors and Conductors, and The American Prize in Opera Conducting.

She made recent debuts at Portland Opera and Opera Columbus, both with Tosca, and at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory with Chérubin. She will hold an Elizabeth Buccheri Opera Residency at Washington National Opera and was previously invited twice to conduct at The Dallas Opera as part of the Hart Institute for Women Conductors. Equally fascinated by the collaborative potential in new music, she conducted the 2022 world premiere of The Puppy Episode at Oberlin Conservatory and will debut at Minnesota Opera premiering The Song Poet. She remains a regular guest conductor in Boston with the Dinosaur Annex New Music Ensemble and ALEA III, as well as having previously conducted Vinkensport, or The Finch Opera and Later the Same Evening at the Boston University Fringe Festival.

Chang was previously Music Director/Conductor for the NEMPAC Opera Project where she conducted La bohème, Così fan tutte, Don Giovanni, Carmen, Fidelio, La Cenerentola, Die Fledermaus, and The Little Prince. Her other engagements include BlueWater Chamber Orchestra, OperaHub, College Light Opera Company, Xanthos Ensemble, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Brookline Symphony Orchestra, Parkway Concert Orchestra, Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra, Northern Ohio Youth Orchestras, among others.

Chang also authors a blog called Conductor as CEO, where she takes ideas from other industries and shares how they apply to arts leaders. Her “refreshing and thoughtful” leadership on and off the podium has led her to become an active speaker and contributor for organizations such as the Canton Symphony, Girls Who Conduct, Sound Mind, Boston Conservatory, Notes from the Podium, PM World Journal, and Routledge Publishing. In 2021, she completed Seth Godin’s altMBA program and joined a unique cohort of global leaders and change-makers.

Having first began her career as a professor, she has served on the artist-faculty at Oberlin Conservatory, Berklee College of Music, Boston University, and Baldwin Wallace Conservatory.

Chang studied orchestral conducting with David Hoose and Bridget-Michaele Reischl; she has also worked with Carlo Montanaro, Emmanuel Villaume, Gustav Meier, JoAnn Falletta, Robert Spano, Gunther Schuller, Larry Rachleff, and Ann Howard Jones. She also studied cello with Amir Eldan, Hans Jensen, and Peter Reijto and composition with Amelia Kaplan and Jeffrey Kowalkowski.

She holds a Doctor of Musical Arts degree in orchestral conducting from Boston University and several degrees from Oberlin Conservatory in cello performance, music education, composition, and music theory.

—

Thank you for the invitation to have a chat. We’ve been in touch for a couple of years now, so this is a nice excuse to actually speak with you!

It really is! Before we start, which Tosca score did you work from?

I worked from the Ricordi. I have my score here if we need to talk about anything specific.

Great. You’ve recently conducted Tosca twice: with Opera Columbus and Portland Opera.

Yes, I was originally engaged to conduct the Opera Columbus production in December 2021. There we had two performances, and I knew about that well in advance. It was in August that I heard from Portland Opera – their production of Tosca was in October, and they needed a replacement conductor. They couldn’t get their Italian conductor into the country because of Covid, and were waiting and waiting to see if the visa would come through. But finally at the end of August they just couldn’t wait anymore because the production period began on October 4th.

Portland Opera contacted me because they saw that I was doing Tosca this season, and asked if I was available. I think the stars were aligned because I could make myself available and was already preparing the work. So I ended up conducting it for the first time before I thought I would. That was interesting – I got to do it twice within the span of two and a half months. The performances from Portland were at the end of October/beginning of November 2021 – there were four scheduled performances (only three happened). Then in December I went to Columbus and did the Opera Columbus production.

They were very different productions of Tosca.

Columbus used a reduced orchestration and their placement of the orchestra is very unorthodox. There was no pit. The orchestra was upstage, behind the singers, but elevated on the second storey of the set. So we were behind and high, on a platform, and there was very little direct communication possible with the singers. I had to use a tiny one rank video monitor – it ended up not being helpful – so I was really conducting blind. I wasn’t able to see any facial expressions because the singers were so small on the screen. I could see where they were but I couldn’t see them breathe – it was really challenging.

In Portland, it was very standard production, with a full 65-piece orchestra in the pit and all the necessary offstage business. We had a huge chorus of at least 30. The stage was also bigger, and the venue is different. It was very eye-opening for me to experience the same piece under such different conditions.

I think I’ve only seen theatre performances with an orchestra at the back of the stage twice. The first time was for the musical Chicago in London’s West End (and the platform was raised), and the second was for Rambert’s Creation. For that, the conductor also had a video monitor, but the orchestra wasn’t elevated in the way you’re describing. It sounds like you had quite a unique experience…

Yes, it’s very unusual. I wish I could have leaned back and seen the stage but I couldn’t because there was a railing and a scrim. I had no visibility of the singers down there, and they only saw me via two little monitors in house way out in the balcony. So yes, it was challenging!

I had to learn to adjust my approach. I like to think of myself as a fairly collaborative conductor, and I treat opera like it’s a huge concerto. So when I am able to, I always like to defer to the singer and give them as much liberty and freedom as I can. But in these circumstances in Columbus, I couldn’t really do that because if I were to hear them, it would be a few seconds late. The orchestra’s sound would also project late because they were elevated and behind, so there would be a massive delay if I were to allow the singers complete freedom. That was a challenge for us to work through.

It was also a challenge to move from the rehearsal room to the performance space. In the rehearsal room there was a fair amount of contact, but we got to the performance space and it was none. We had to get used to the acoustics, and then figure out if could I get an audio monitor so I could actually hear the singers clearly. For one of the dress rehearsals I couldn’t hear the singers at all, and this piece really doesn’t play itself.

There are also some very important choreographic moments, for example, Scarpia’s death or Tosca’s suicide. How did you deal with all of that in this situation?

Well, there are definitely musical cues for the singers to be able to pace themselves in their stage movement. But there are also moments in which I try to time the music to the actions on stage – one being when Tosca places a candle on either side of Scarpia after his murder, and places a cross on him. That’s timed with iterations of the Scarpia theme. It was fairly easy for me to do in Portland. There was time for me to think, ‘OK, Tosca’s moving there so I’m going to slow it down a little bit so that she has time to walk to the other side and place the other candle down…’ That’s simple… if I can see them!

It sounds like you needed to lead the singers more than vice versa.

Right. I think it really depends on the nature of the music, and that decides which party should be the leader in crafting that narrative.

‘Who’s the boss?’[1]

Right! And it’s not always the conductor. I always like to err on the side of allowing the singers to take charge, because there’s a myriad of things that could happen on stage that could affect the timing. If there is space in the music that allows me to be free, then I’m going to give them that space. It’s always easier when you can be in proximity with the people on stage, then you can have constant contact and react and collaborate with each other in the moment.

What I love about opera is that it’s different each time. I’m a cellist, so I come from a symphonic, orchestral background. Having grown up in the orchestral concert space, I feel that there’s a lot I learned from conducting opera. In the symphonic space there’s a tendency for us to aim for that one specific interpretation. We say, ‘OK, that retardando is going to go from this metronome mark to that metronome mark, and if we don’t hit it then we didn’t make it, we’ll try again next time’.

In opera there’s no way to have that kind of precision from show to show, even if it’s back to back, with the same singers, and the same orchestra. There are just so many other factors that can be different. When I first started doing opera that was a lesson for me to learn, and it allowed me to see symphonic music differently. What if I missed that metronome mark by two points? Is that considered wrong? Or am I responding to the specific needs and conditions of that day, and that hall with that acoustic? That will allow the music to be in its most coherent form on that day. I gained a lot from not being able to have that rigidity; it’s just not possible.

How many people did both venues seat in the audience?

Portland seats around 3,000 and Opera Columbus was 925.

I have some pictures, in fact I’ll share. This is the Portland venue. The pit is huge – and there are two balconies.

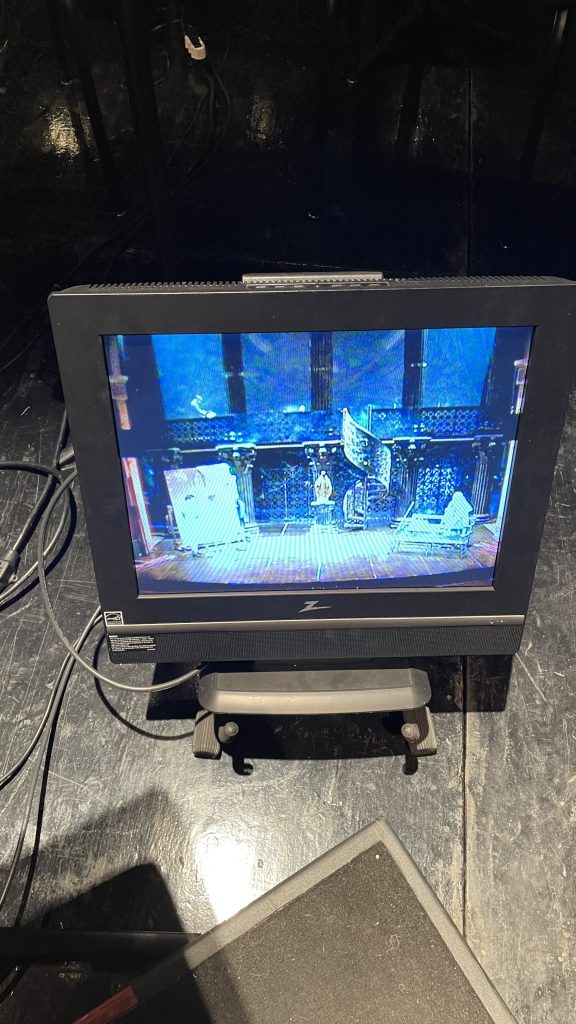

Here’s the Columbus Tosca – we were up on the balcony.

This is where I stood – stage left, with the scrim. And that was what I could see from the balcony… which was basically nothing.

That’s the video screen I had. It’s in colour but it’s tiny, and on the floor.

Wow, that is such an unusual set-up! Thanks for sharing those.

In your academic work you have focused a great deal on leadership and have your own blog ‘Conductor as CEO’ as well as regularly posting on social media.[2]

You conducted Tosca in two dramatically different scenarios. Did you find your leadership style changing?

I did. The two orchestras were very different. In Portland it was the Portland Opera Orchestra, and in Columbus it was a professional chamber orchestra that Opera Columbus partnered with for their productions – ProMusica Chamber Orchestra.

When I started rehearsing the Tosca production at Portland Opera, the orchestra had not played together for about two years, so I felt I had to help with the re-entry. Even though they knew the piece very well (probably better than me as I was conducting it for the first time) they had to remember how to play together again. I remember the first rehearsal being a little rough because it was like warming up the car – there were a few kinks to work out. The second half of that first rehearsal felt much smoother but I had to make sure I didn’t put it on myself or on them. I actually articulated that, and said out loud that I realised that we just haven’t played together and this is why it’s hard. We just kept working at it. What I’ve learned is that sometimes, pointing out the elephant in the room dispels a lot of the tension, worry and anxiety – not that it dispelled all of it but it just made me feel part of them and not separate or against them.

We had fewer services than usual, so our rehearsal time was already limited. There was also a bigger orchestra, it was the full 65-piece orchestration, so there was a lot of difficulty due to the mass of people. It’s very different conducting a larger orchestra than a chamber orchestra, which was the case in Columbus. In Columbus we had a 27-piece orchestra. We hired a reduced score, so a lot of my work was managing that. But what I found really interesting was that this orchestra is a collaborative chamber orchestra, and they play together all the time. They are comprised of musicians that come together a few times a year from all over the country, so a lot of them are not local. When they are in Columbus they have host families that they stay with, the orchestra puts them up. But it feels like it’s more of a collective – they have all the hallmarks of a conductor-less chamber orchestra. They are very good at communicating and listening to each other, and because they’re a smaller group they can really do that.

So when I was on the podium I had to conduct, and lead, differently – the finesse that the Columbus orchestra had as collaborators saved the day. If they weren’t as in sync and attuned to each other, I couldn’t have devoted as much of my mental capacity to managing the challenge of the logistics. The orchestra was able to respond and collaborate with me in a very ‘in-the-moment’ way, and it felt very different to conducting the Portland Opera orchestra (not that one was better or worse, they were just very different experiences).

Naturally, I had to adjust how I was leading. Working with the Columbus orchestra inspired me to take some risks in how I gave notes. I had less rehearsal time there so the only way I could rehearse specific sections was to give them typed up notes at the beginning of the rehearsal. Near the beginning of Act 3, at fig. 4 on p.370, there is one of the most beautiful orchestral passages – it’s a chorale with some really special counterpoint in the strings that I had never had a chance to rehearse. It’s the interlude after the Shepherd Boy theme and there are the various offstage bells sounding with the chorale in the strings. It always got pushed down the list because it was not critical. We only needed a minute to rehearse it, but we never had that minute and I knew that the orchestra had the capacity to bring it out.

I would not expect the players to know about the counterpoint, so I actually annotated that page of the score, highlighted the motive in colour and showing how the counterpoint was a composite of multiple lines, which was not evident in the individual parts. I said that it would be great if we could bring this out. I felt comfortable sharing this kind of detailed note – I think it’s because I was responding to how they were so attuned to each other. I took a risk in doing that, knowing that it might not resonate with them.

In Portland I actually had time to rehearse this spot. I was glad that I did because I’m not sure the note I gave in Columbus would have resonated in the same way. I probably would have shared this insight differently because they’re different people with a different culture. That’s what fascinates me – I can be the same person wherever I go, but the leadership has to adjust, it’s never the same.

How did the offstage bells work in these productions? [Act 1 Finale ‘Te Deum’ p.172-188, and Act 2 fig.4-8 p.370-376]

Ah, the bells! There are different pitches, and bells are indicated by distance – the score indicates which bells are really distant, which are medium distant, and which were closer [meno lontano, meno vicino, più vicino etc.]. The idea is to create this sense of surround sound, depth and distance. The percussionists set up the bells backstage – that’s usually how it’s done. They’re offstage with the monitor and just play it themselves. That’s what Portland was like – the theatre allowed for it.

In Columbus, because of our strange set up, there was no offstage – we were basically offstage already! We had the reduced score, so there was only one percussionist instead of three. So Columbus used audio files of the actual bells in Rome (other productions have used them as well). They had all of the individual pitches and the bells were played by the stage management as sound cues. I had to rehearse with the stage manager who was calling the cues for each of those bells – that was a real challenge for her.

So you were conducting the stage manager?

Well yes, I was. She could see me via the monitor. We had to rehearse that because there was a delay, and she was not the one who triggered the sound effect – she was on the headset calling the sound people to trigger the sound. She had to anticipate in order for the sound to be heard at the right time. It was really amazing that she was able to do that! Every bell pitch had a different sound file, so each pitch had its own sound cue. So that was interesting – the productions were wildly different. It was almost like working on two different pieces of music.

There is also the offstage chorus in Act 2. How did that work for you?

Yes, that’s near the beginning of Act 2, during the interrogation scene. It starts at p.213 (fig. 13). Tosca and the chorus are singing in the performance that’s happening outside the window of the room where the scene takes place – hence they are offstage. Spoletta opens the window, allowing the music to be heard. You’ll see that the offstage chorus is in 4, basically singing a homophonic chorale, and the principals’ scene music remains in 2. The principals are singing over it in a different meter. It’s interesting how Puccini has notated it in that way. I think it offers a sense of distance and also this sense of overlay and layers, as opposed to one block of sound. It has a psychological effect, and is brilliant from a compositional standpoint.

We had a chorus sing offstage for both productions, and I had an assistant conductor who conducted them both times. The Columbus production had very limited backstage space (the wing space was very small and the orchestra was already sort of backstage in that upstage area) so it was challenging for us to figure out where to put them. Logistically, I had to think about whether I followed the chorus. Who is the leader here? I thought we should maybe go with the chorus to align things because the orchestra is very bare. There’s just the pizzicato bass line. My original thought was that the singers can hear the chorus so they could try to be with them, and my job in the pit could just be to help the cellos and the basses be with everybody else.

For each production it was a bit different – we had to figure out how the timing worked with the acoustic and where the orchestra was placed. We tried different options, but decided there could be potential for confusion and chaos if there wasn’t one central point – the principals on stage wouldn’t know who to watch or listen to. It made more sense for me to conduct, and for the assistant conductor to conduct the chorus (and to conduct ahead of me so that we were together). Then the principals, cellos and basses could follow me. That’s what I learned from experimenting, it’s a fascinating section. I’d never done it before so I wondered what would happen if we catered to the chorus. In theory it made sense – maybe there’s a world in which that could work too – but it turned out that the more conventional way is the way that works.

So, it’s conventional for a reason.

Yeah, right! I just had to try it – interesting to now be reflecting on it.

How did collaborating with a director change how you worked? That is one huge difference to symphonic performance.

Both directors were very collaborative, I was grateful for that. The director in Portland was very experienced with this piece, and the one I worked with in Columbus was doing it for the first time, so it was great for me to hear two very different perspectives. One of the things I actually love about opera is that I don’t get to be the only cook in the kitchen. I don’t feel such pressure of being the one who has all the answers – I like being part of an artistic leadership team, rather than just being the sole artistic leader. I leaned on the stage director quite a lot – I’m always open to their ideas in the stage rehearsals.

I’m not the kind of conductor who shuts things down because I’m afraid that it won’t work or that it’s going to be too hard for the singers, or myself. I think there’s a lot of fear and defensive protection that can happen when you have two major leadership forces in the room together, so in stage rehearsals my intention is to understand their ideas, and let them do their work. It’s really the stage director’s rehearsal – I’m there as a facilitator.

At the same time I think it’s important that I’m there as an advocate for the singers, and I will speak up for them if something that I see is not going to serve them and allow them to do their best work. In other productions I have helped singers out when I discover they’re being staged to sing an aria mostly upstage so their sound will be buried, or not in the best physical position to allow them to breathe properly. I’m always on the lookout to advocate for singers in that way, as mindfully as I can, but I always try to let the stage director do their job first.

That approach worked out for the stage director and I in both productions. They were always open to having a dialogue: what do you think about this? Why do you think this phrase exists in this way? Why do you think Scarpia says this? Why do they do this? I think it’s those conversations that actually add to how I can shape or execute the music to serve this particular narrative. The narratives can be very different from production to production, and I have my own expectation of what the musical gestures mean in a meta-artistic sense, based on my study of the score. So it’s good to have those conversations and see things from different perspectives.

There are so many transitions – in the orchestral recitative especially, the music frequently changes within very short spans of time. Are there any particularly difficult transitions for you as the conductor?

Hmm. Actually, I think that Puccini writes music that is very organic, so even though there are these drastic changes in tempo, character or style, or whether it’s more recitative-like, aria-like or any shade in between, I think it always makes sense why he’s doing it that way. It just flows well and I found that navigating that was not really a challenge. I think allowing it to be more spontaneous was more difficult, to really feel like it’s being made up in the moment – it’s like a film score in that sense. Every musical gesture can be attached to an action, a thought, a lighting cue or dramatic event. We can assign meaning to every musical gesture, and it’s sometimes a challenge to make all of those things align. What is the singer doing? What am I seeing that they might be doing a little differently? Am I waiting for that thought or that expression to change before I start this music? Or is the music that I prep the trigger for them to do something?

It’s also about deciding whether it is the music that triggers the singers or whatever the singer is doing vocally or dramatically that triggers the music. How do we navigate that? I think that is the key to recitative conducting, and in Puccini I think it’s the key to all of it! Regardless of whether it’s recitative or aria, everything has that though process behind it.

Sir Antonio Pappano is a Puccini lover. In a Royal Opera House interview[3] he spoke about the composer’s natural sophistication in theatre, and his amazing sense of timing. None of his operas are too long.

Yes, they’re perfect. The perfect length.

One aspect he said was difficult is how Puccini often doubles the singing line with the violins, and that gives you a lot of balancing issues. That is definitely heard in Tosca, as well as La bohème and Manon Lescaut.

Yes, absolutely. It gives you co-ordination issues, too. What I find really interesting is that formally, if you look at arias or when Puccini sets up the scene, it’s often in AA form – there’s an orchestral version of the music, and then that music is repeated with the singers. I find that consistently in his music. Puccini’s not the only composer who does that, but he does it very regularly – I’m curious about how the singer’s performance of their aria or scene impacts how I conduct the orchestral version of it. How do I get that continuity?

As someone who comes from an orchestral background, I care a lot about form. Actually, sometimes I struggle to not be so rigid about it, because I’m always thinking about the form of the music and how I assign function to every single phrase. But sometimes there is no function, it’s a transition, but I really want to make some meaning out of it. Sometimes in Puccini that just doesn’t work, and I think that aspect is what makes it so organic. It’s not structured in that way.

I’m the opposite. Sometimes I look for the narrative where there is none in music that is more formal.

Sure, it can work the other way too. Everything in moderation, or a combination of both, is helpful.

In the Tosca and Cavaradossi duet in Act 1, there are some moments in which the music is lyrical and aria-like, for example p.52-3. There is an interlude between what ends on p.52 and what starts again on p.55. It’s very action based and recitative-like, and it’s dramatically very charged. On paper it may not look like it’s challenging, but for me it’s also about the dramatic details. For example, at fig.27 (p.53), what is that [sings] ‘barm barm barm’ doing there? Why did he write that? Is it connected to Tosca’s line, or related to Cavaradossi’s? I think its Cavaradossi’s line. She’s teasing him and saying ‘wait for me at the stage door and we’ll go to the villa alone’. She sings ‘soli, soletti’ and the ‘barm barm barm’ in the next two bars is Cavaradossi’s shock.

I try to time that with the singer’s expression, and I talk about it with the singer in rehearsal. I say, ‘in my opinion those bars depict your reaction, so whatever you do, be clear about this reaction!’ Then that music will impact the moment he sings ‘stassera’. That little theme also has a diminuendo from a forte into a piano, so I ask myself why is it there? Why is it not forte all the way through? It’s like there is shock and confusion. There are these little spurts of really telling drama that make it organic and movie-like, and we can assign meaning to all of those.

I think these three pages are a good example of a dialogue and the underlying subtext that is not said. What words are not being said, in between the lines? They are perhaps represented by the music.

It’s almost like ‘mickey-mousing’ at that point.

Yeah, right! A lot of this music is very cartoonish. That’s why it’s dramatically effective, but also challenging because sometimes I get stuck thinking about the music in one way. The staging process can help me dislodge it and the stage director and singers often change my mind. I’m getting better at feeling really comfortable having those conversations.

You mentioned that the music is almost ‘cartoonish’ – the emotion and action is very much at the surface. However, it has been said by Tito Gobbi and Bryn Terfel (both famous Scarpia interpreters) that it is best to underplay him.

Tito Gobbi, writing for the Tosca Cambridge Opera Handbook wrote: ‘during an unsatisfactory rehearsal, I suddenly sang words and music without anything of personal interpretation added – and all at once the great effect was there! Puccini had already thought of everything, I discovered. All I had to do was be faithful and humble’ (Gobbi 1985:80).

More recently Bryn Terfel, in Antonio Pappano’s Classical Voices documentary (No. 4), said a similar thing (in a rather more British way): ‘It can come back and bite you in the bum if you throw yourself too much into this demonic aspect of a portrayal, of acting of the stage. Sometimes it’s just better to take a step back, not dive too much into creating a persona on stage’.[4]

Do you have to approach the score in a similar way when you conduct it?

It’s so fascinating that you found those two similar perspectives. I think so much is already written into the blood of the music – there’s so much instruction that’s on the page, in notes and words. It’s true that if we just follow the music faithfully and stay true to all the instructions that’s a great starting point. I think that we can over interpret, but I can’t even keep up with the interpretation that’s already written on the page! I always find that with Puccini, there is so much information that my mental capacity is often filled up without being able to care for everything that is in the score.

I really resonate with those perspectives. I do think that the score has the answers and it’s all laid out there, if we’re mindful enough to study, wonder, discover, make connections and be curious about the intention behind why Puccini wrote these words that give direction or emotional interpretation.

Something that’s very small but extremely important is on the very first page of the opera. The chords open the opera and then immediately you have this hurried music that depicts Angelotti’s urgency and his escape. If you look at the start of the 2/4 section and the articulation markings of the first two bars you have the [sings] ‘bar, bar, babarm’ with the carets. Then you have it again but with accents and the staccato marking. If you look at the next page, it then becomes tenuto. I often hear recordings where orchestras just play all the accents in the same manner, but I’m curious about why Puccini decided to do that.

The way I interpret it is that it’s a winding down of energy.

That’s exactly what I was thinking.

Right. Angelotti’s tired, so there’s a burst of energy and then a dragging of the feet. I was really particular about trying to get the orchestra to really play the caret plus the accented version for the first two bars and then the downgraded levels of that. There’s no diminuendo, but a petering out of the orchestration – the sense of losing steam. That makes it very cartoonish. And then at fig. 1 (p.3) it’s like a balloon that now has no air in it. I think trying to play everything that’s on the page is so important in setting up Angelotti’s line.

Given the clues on the page, I can imagine that that was what Puccini was thinking. But I found that really hard to get people to do, because it’s so fleeting. It’s less than one second of playing, yet I’m convinced that it can give the musicians so much more agency if they’re willing to take the leap with me and add this kind of depth. It’s a very little thing, but there are so many of those in the score. In that sense I can never be done with uncovering what’s on the page. I really do see it like a movie. How am I setting the scene? What is the scene that’s happening? How do I use the music to portray that?

It seems that Sardou’s play, La Tosca, was not looked upon favourably by a number of Puccini’s collaborators. For example, Giacoso, one of Tosca’s librettists, detested it, and objected to its ‘“absolute inadaptability” to the musical stage’ (Wilson 1997:113). He wrote to Ricordi: ‘the first act consists of nothing but duets. Nothing but duets in the second act, except for the short torture scene in which only two characters are seen on stage. The third act is one interminable duet’ (p.113).

Ricordi, Puccini’s publisher, initially complained that the Act I duet between Tosca and Cavradossi was ‘a duet of little pieces traced in small lines which diminishes the characters’ (cited Budden 2002:194).

Do these features cause you any issues?

That’s interesting. I don’t see it as diminishing the characters, I just think Puccini puts more weight on the relationships between the characters and the ramifications of those relationships. In a lot of the research I’ve done for other operas, I always find scholars talking about an opera being an ‘ensemble piece’, or an ‘aria-heavy piece’, so I definitely see why someone would make that kind of observation with this opera. I agree, there is more ensemble than aria work, and even the arias are embedded within scenes – they’re fleeting moments in a very through-composed work. Puccini is so good at the organic nature of this through-composed work that it’s as if you know what’s going to happen before it happens.

Yes, I think that’s true even when the music completely changes.

Yes, I rarely find a moment where the harmony is jagged or the transitions don’t quite make sense. It always seems very organic.

I think that the character of Scarpia is so interesting. Sometimes I joke, at least from a purely musical standpoint, that this piece should be called Scarpia: the opening chords are the ‘Scarpia chords’. Puccini uses this leitmotif method of recalling characters or moods with his themes, and those three opening parallel major triads of B flat major, A flat major and E major are so embedded in the piece. There is so much connotation in the choice of those chords (there’s a tritone between B flat and E), and then he uses them again and again, more than he uses Tosca’s own leitmotif.

I don’t see Scarpia as a kind of maniac – I think he has a lot of self-discipline and self-control, and that’s seen in the ‘Te Deum’. A lot of what he’s singing is really nasty, but it’s housed within this very poised and matter of fact demeanour. It’s actually more scary and sinister for the character to be played with a veil, and with composure. So when he does these awful things it’s so scary that he could appear so disconnected. His outward demeanour is reflected in the music. When he gets stabbed and dies at the end of Act 2 those Scarpia chords return, but the E major chord becomes E minor (fig.65 p.355-356). That’s a very clear manipulation of harmony on Puccini’s part.

As if the sky changes colour suddenly.

It’s like his spirit floats away.

The characterisation is so interesting. I know that different artists bring different interpretations and perceptions to the roles, but I often think about approaching a piece from a purely archaeological standpoint i.e. thinking of the score itself as the artefact, and what can we learn from it.

The characters are very ‘real life’ – the themes in this opera are universal and relevant. They are timeless. Every woman can relate to the jealousy that Tosca feels, there are going to be artists and activists like Cavaradossi at every point in history, as well as police corruption and the psychopathic, abusive person in power. In a way, this is the perfect opera.

Bibliography/Recommended Reading

Budden, J. Puccini: His Life and Works (Oxford University Press, 2002)

Gobbi, T. ‘Interpretation: some reflections by Tito Gobbi’ in Carner, M. Giacomo Puccini: Tosca Cambridge Opera Handbooks (Cambridge University Press, 1985)

Puccini, G. Tosca Full Orchestral Score (Ricordi)

Wilson, C. Gaicomo Puccini (Phaidon Press Limited, 1997)

In Conversation with Antonio Pappano, Music Director of The Royal Opera https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BeB0uR2rzsA&t=687s (accessed 27th January 2023)

BBC2 Pappano’s Essential Tosca First broadcast on 21st January 2012 5.30pm (no longer available)

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b018nvw3

BBC 4 Pappano’s Classical Voices Episode 4: Baritone and Bass (no longer available)

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0638jby

[1] Conductor Brett Mitchell used the ‘Who’s the Boss?’ analogy when describing conducting a concerto. Click here to read his interview with Notes from the Podium on Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F.

[2] https://www.conductorasceo.com/ and her article for Notes from the Podium, published in October 2021.

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BeB0uR2rzsA&t=687s ‘There’s a natural sophistication in Puccini, even though he’s manipulating you from note 1, because he was one of the great theatre musicians. He knew how to write for the theatre. He knew about timing, none of his operas is too long’ (6m47s-7m06s).

[4] (3m25s-3m45s)